Database Pattern: Memberships & Invitations

Posted on Nov 2, 2024In which I present the first of several reusable and adaptable patterns for common application requirements. The patterns are intended for prototypes, mvp projects, or small hobbit scale projects that won’t see more than a few thousand users. These came about from my experience working on a project that evolved rapidly in an ad hoc fashion. Your application code can be as shitty as you like - refactoring it is a lot easier than refactoring your data model once it’s started filling with production data. Worse still, the data model you choose has a pervasive, subtle, and far reaching effect on how the code is written. This is especially true for code written at speed. Getting the data model correct to begin with saves a lot of pain later. It also makes it easier to extend and update without major migrations.

Without further ado, here’s the first of these patterns - Memberships and Invitations. This pattern is the basics you’ll need to support collaborative features such as teams, or a notion style “share with user” for a specific document (or other resource).

Requirements

The database schema solution for memberships and invitations should enable the following at a minimum:

- Memberships can grant access to either a single specific resource, or to a group of resources

- Invitations must work seamlessly whether the invited user has an existing account on the platform or not

- The schema must be easily extensible for adding features such as expiring invitations or more complex forms of access controls at a later date

The Pattern

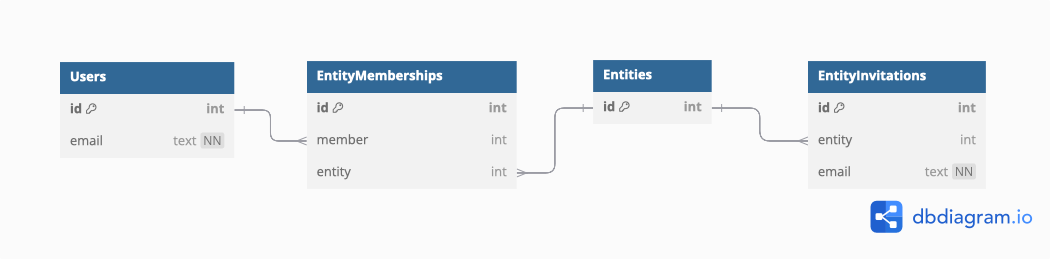

The pattern is simple - EntityMemberships and EntityInvitations.

Here’s the DBML model for the pattern:

table Users {

id int pk

email text [not null, unique, note: "Always lowercase"]

}

table Entities {

id int pk

}

table EntityMemberships {

id int pk

member int [ref:> Users.id]

entity int [ref:> Entities.id]

Indexes {

(member, entity) [unique]

}

}

table EntityInvitations {

id int pk

entity int [ref:> Entities.id]

email text [not null]

}

The Users and Entities table are deliberately sparse - these tables are use case dependant, and are not relevant to the pattern beyond providing an id and a user identifier (email address). The remaining tables, EntityMemberships, and EntityInvitations demonstrate the pattern.

I have deliberately omitted adding a creator field to the Entities table. It complicates the access controls by having two different places where access privileges are granted. By granting the creator a membership, it keeps the access checks to a single table. If tracking the creator specifically is a requirement, this can be added to the memberships table as an enum (creator, collaborator, etc), or to an event log table for tracking changes.

The EntityMemberships table has a composite primary as opposed to a simple id int pk field to identify records. The benefit of this approach is that it prevents a user having multiple membership records for the same entity, and that it does this at the database level. The less a programmer has to remember when coding, the better. The additional complexity in joins is worth it to prevent errors of omission in the implementation.

The EntityInvitations table is fairly simple, like the rest of the pattern. We cannot just link to a Users record since it’s a requirement that users not need an account to be invited.Therefore, the invitation must store a unique identifier such as email address in order to link to an existing account, or to an account created as part of the invitation flow.

In the current form the invitations records are intended to be deleted upon acceptance/rejection of the invite. The EntityInvitations table can be extended to include a link to Users record after acceptance, the date the invitation was accepted/rejected/expired, and so on. Starting from a simple base pattern allows multiple features to be painlessly added later.

Extending the pattern

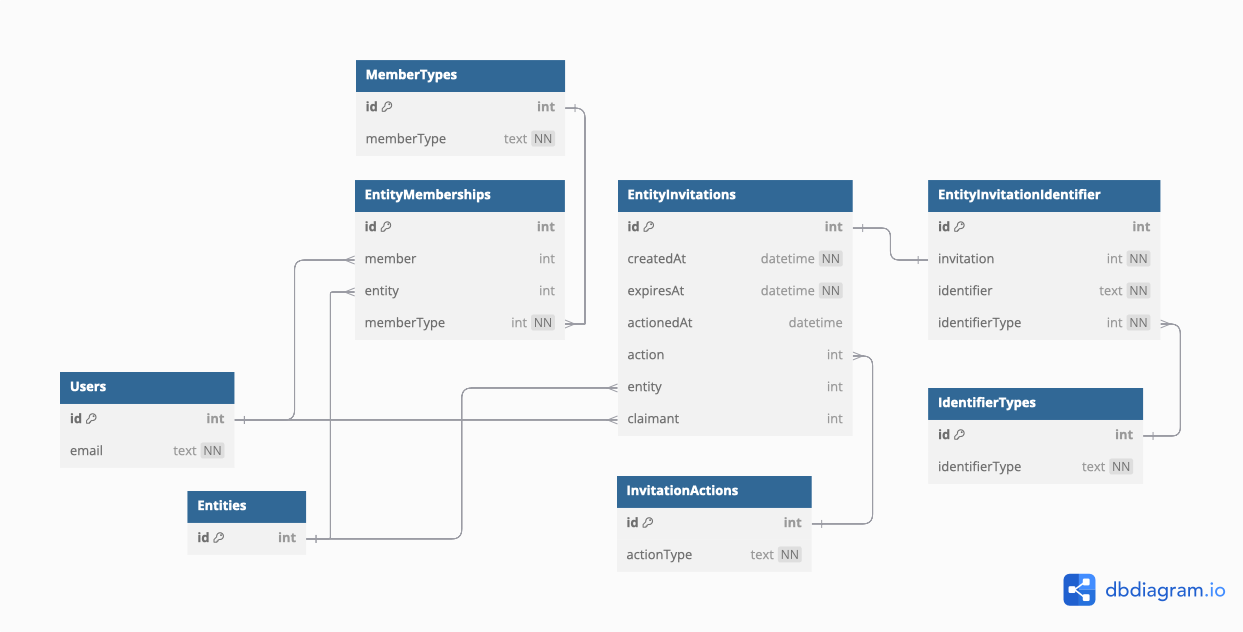

Now that the base pattern has been established, here is an example of how it could be extended. The extension below supports multiple identifier types for users - email address, mobile number (for sms), and arbitrary invite code. It also implements invite expiration, simple membership types, and linking invite to the Users record after acceptance (to cover the eventuality of a user changing their identifier).

In this extension, each invite can have only a single identifier. If the use case required it, this relationship could be change from 1 to 1 into 1 to many. This would allow the inviter to add multiple identifiers.

table Users {

id int pk

email text [not null, unique, note: "Always lowercase"]

}

table Entities {

id int pk

}

table EntityMemberships {

id int pk

member int [ref:> Users.id]

entity int [ref:> Entities.id]

memberType int [ref:>MemberTypes.id, not null]

Indexes {

(member, entity) [unique]

}

}

table EntityInvitations {

id int pk

createdAt datetime [not null, default:`now()`]

expiresAt datetime [not null]

actionedAt datetime [null]

action int [ref:>InvitationActions.id, null]

entity int [ref:> Entities.id]

claimant int [ref:>Users.id, null]

}

table EntityInvitationIdentifier {

id int pk

invitation int [ref:- EntityInvitations.id, not null]

identifier text [not null]

identifierType int [ref:>IdentifierTypes.id, not null]

}

// Lookup tables Definitions

table MemberTypes {

id int pk

memberType text [not null]

}

table InvitationActions {

id int pk

actionType text [not null]

}

table IdentifierTypes {

id int pk

identifierType text [not null]

}

Example Usage

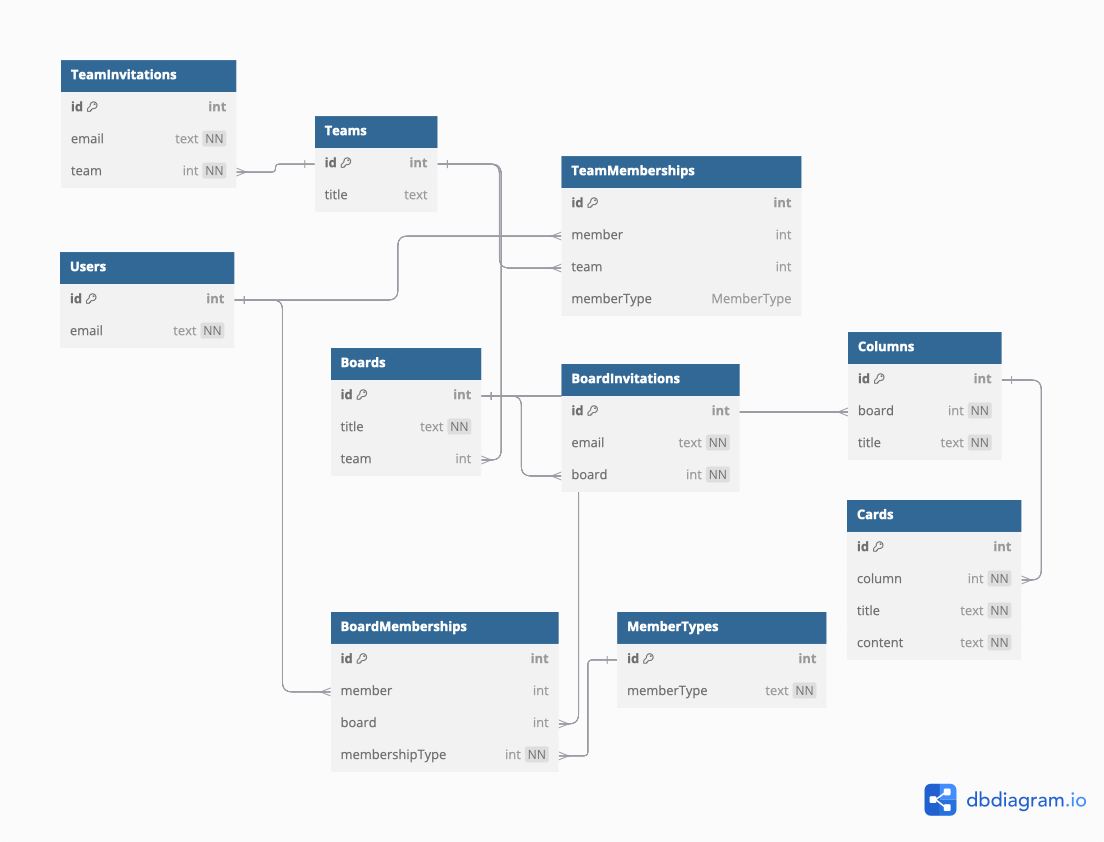

So far the schemas presented have been for a theoretical “Entity”. To demonstrate the application in a more real way, here’s the schema for ZenKanban. ZenKanban is a trello clone, supporting simple team based collaboration, as well as collaboration on specific boards.

table Users {

id int pk

email text [not null, unique, note: "Always lowercase"]

}

table Teams {

id int pk

title text

}

table TeamMemberships {

id int pk

member int [ref:> Users.id]

team int [ref:> Teams.id]

memberType MemberType

Indexes {

(member, team) [unique]

}

}

table TeamInvitations {

id int pk

email text [not null]

team int [ref:>Teams.id, not null]

}

table Boards {

id int pk

title text [not null]

// If there's no team relation, it's a private user board

team int [ref:> Teams.id, null]

}

table BoardMemberships {

id int pk

member int [ref:> Users.id]

board int [ref:> Boards.id]

membershipType int [ref:> MemberTypes.id, not null]

Indexes {

(member, board) [unique]

}

}

table BoardInvitations {

id int pk

email text [not null]

board int [ref:>Boards.id, not null]

}

table Columns {

id int pk

board int [ref:> Boards.id, not null]

title text [not null]

}

table Cards {

id int pk

column int [ref:> Columns.id, not null]

title text [not null]

content text [not null]

}

// Lookup tables

table MemberTypes {

id int pk

memberType text [not null]

}

Concluding remarks

It is important to bear in mind that this pattern is intended for an MVP, or for small scale apps. The approach for larger and more complicated apps is likely to differ from this. As always, one must design for the requirements in front of you, not for some mythical future complication. Keeping it simple keeps you sane later. In practice, the requirements you envisioned will not come to pass. Instead, you’ll end up with a different but equally complicated set of requirements, and evolving the schema becomes that much harder.