Database patterns: Inboxes & Notifications

Posted on Nov 10, 2024The second pattern I’m adding to my toolkit is one that implements change notifications, and a user inbox. Examples of this type of feature are ubiquitous, for instance - Github, Linear, Hardcover, and Substack. Having a proper pattern for collecting this kind of data is useful for more than just notifications. If done correctly, it can be built off to create a change log feature, or a restorable revision feature.

Requirements

The basic features for an inbox & notifications pattern are that it should:

- Support efficient creation of a notification for all resource subscribers. This should be an O(1) operation.

- Support read, and unread notifications, so that users are not shown irrelevant notifications. A user must be able to easily toggle a notification’s read status.

- Support per user notification deletion. A user’s inbox shouldn’t fill with read notifications. This should be undoable, and it should not affect other subscribers to the event that caused the notification.

- Provide a simple method for implementing notification suppression if the app implements presence detection for an entity.

The Pattern

The pattern for notifications consists of 3 tables:

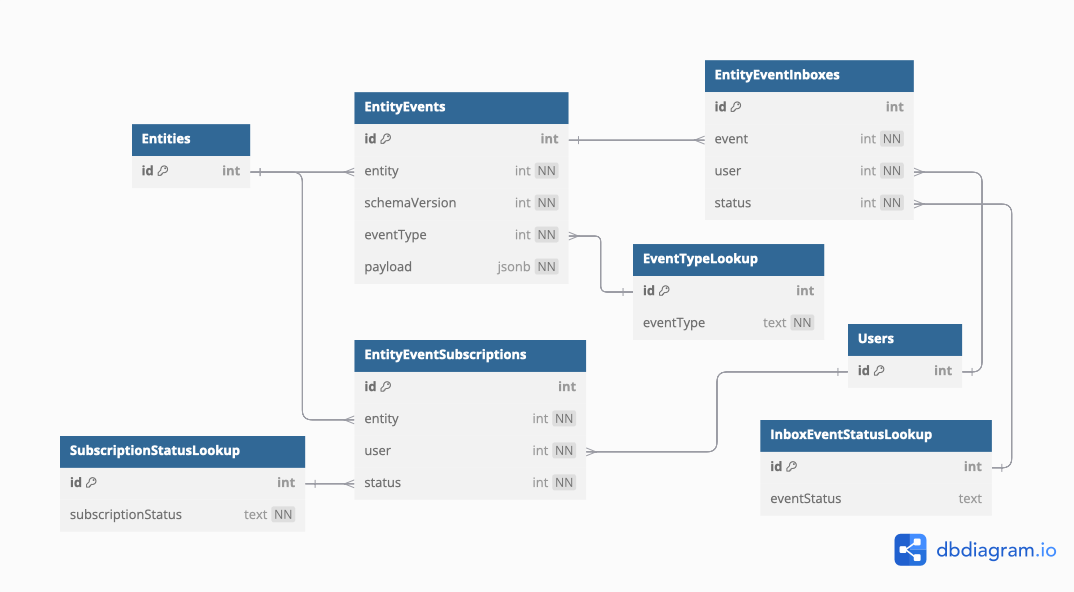

EntityEvents- The heart of the pattern. This table is an event log that stores each change made to the entity it tracks.EntityEventInboxes- The inbox records allow us to track notification status individually for each user. It also provides a high water mark for determining which events have occurred since the last time the inbox for a user was updated.EntitySubscriptions- The subscriptions record make a referential link between a user and an entity that they’d like to subscribe to be notified of changes to.

The schema diagram

The DBML for the pattern

table Users {

id int pk

}

table Entities {

id int pk

}

table EntityEvents {

id int pk

entity int [ref:> Entities.id, not null]

schemaVersion int [not null]

eventType int [ref:>EventTypeLookup.id, not null]

payload jsonb [not null]

}

table EventTypeLookup {

id int pk

eventType text [not null]

}

table EntityEventSubscriptions {

id int pk

entity int [ref:> Entities.id, not null]

user int [ref:>Users.id, not null]

status int [ref:>SubscriptionStatusLookup.id, not null]

}

table SubscriptionStatusLookup {

id int pk

subscriptionStatus text [not null]

}

table EntityEventInboxes {

id int pk

event int [ref:> EntityEvents.id, not null]

user int [ref:>Users.id, not null]

status int [ref:>InboxEventStatusLookup.id,not null]

Indexes {

(user, event) [unique] // Each user only has a single record per event

}

}

table InboxEventStatusLookup {

id int pk

eventStatus text

}

Discussion

Entity Event Subscriptions

In order to track who receives what notifications, we save a set of subscription records for each user. These subscriptions link user with entity, and manage the subscription status.

The application layer can add these records either at an explicit user request (such as Github’s “watch this issue”), or implicitly when a user creates an entity.

All notifications are dependant on the user having a subscription record for the entity. This ensures that there is a single place to check for subscriptions. The alternative whereby you have a creator field, and a subscriptions table means the chance of error is higher as you’ve just enabled corner cases (what if the user wants to unsubscribe from an entity they’ve created), and split the canonical record into two places.

Entity Events

The EntityEvents table contains the log of events for all actions performed on the Entities table. The base pattern described here utilises a payload field with a json datatype.

It is important to note that the use of an int as the primary key is not arbitrary. While you could use a uuid here, having an autoincrementing id field means that we get event insertion ordering by default (since this type of key monotonically increases). If you wish to use a non-incrementing key type, you could also add a datetime field to preserve insertion ordering.

If the use case is extremely simple, you could consider normalising the payload schemas into separate tables linked 1:1 with an EntityEvents record. However, this rapidly becomes complex and unwieldy for all but the simplest use cases.

Instead, we are creating an event log for each event generating entity. Along with the event payload, we’re tracking metadata on the event - schemaVersion, and eventType. These fields will allow us to implement a migration strategy for handling existing event data when the schema is updated.

For smaller apps, this kind of event log pattern has a few benefits. The speed at which we can evolve the event schemas is increased as a database migration isn’t needed for each change. The schemas can easily be normalised into a set of tables later if desired. It keeps the complexity of the application, and the data model low, and avoids needing to add a dedicated document store for event data. More usefully, this pattern allows us to enforce referential integrity on the entities that the event pertains to.

As an approach, it is not without its downsides however. The database is less able to enforce data integrity over a json field, transferring that responsibility upstream to the application layer. Schema versioning is also a concern - instead of uplifting the entire structure with an SQL migration script, we need a slightly more detailed approach to event schema versioning.

The speed for querying json fields in a relational database is also typically lower than in a NoSQL document store. While it’s not low enough to bar this approach, it does mean that more complex queries such as on demand report generation over a large quantity of events are now less performant.

Migrating older events can take one of a few approaches.

- Redrive the event log - use a long running script to load, migrate, and save each existing event so that the entire event log is always no more than 1 version behind at most (and typically always at the current version). This means your API service code is kept lean as at most you only need to keep the code for the current schema and the previous schema deployed (until the event log redrive is complete).

- Migrate on demand - when a user requests data from the event log, run a migration function and save it. This has the advantage of not requiring the more complex orchestration of redriving. The downside is that you’ll likely never fully migrate the database - some users will never return. Your migration function will also slowly grow in size as schema versions are bumped.

- Just don’t migrate - At the cost of increasing your API service code, you could just not migrate. If a user requests old event data, they get the old event data presentation. This is very much dependant on what the events relate to as to whether it is a fit for your use case.

Entity Event Inboxes

The inbox records allow the system to track the notification status for each event and user. We can mark an event as read or deleted without affecting other users notifications. The inbox records also function as a high water mark for events that have been processed for a given user. If a set of events have occurred since the last inbox record (as determined by creation date or id value), they should have inbox records added. This can occur when the request for the inbox is made. To handle a large amount of unprocessed events, the application layer should implement a paging solution. If the application is presenting the inbox with pagination, there’s no need to process all the events at once, just the events for the requested page. If this kind of performance corner cases becomes an issue, a job queue to check and process events autonomously would also be appropriate.

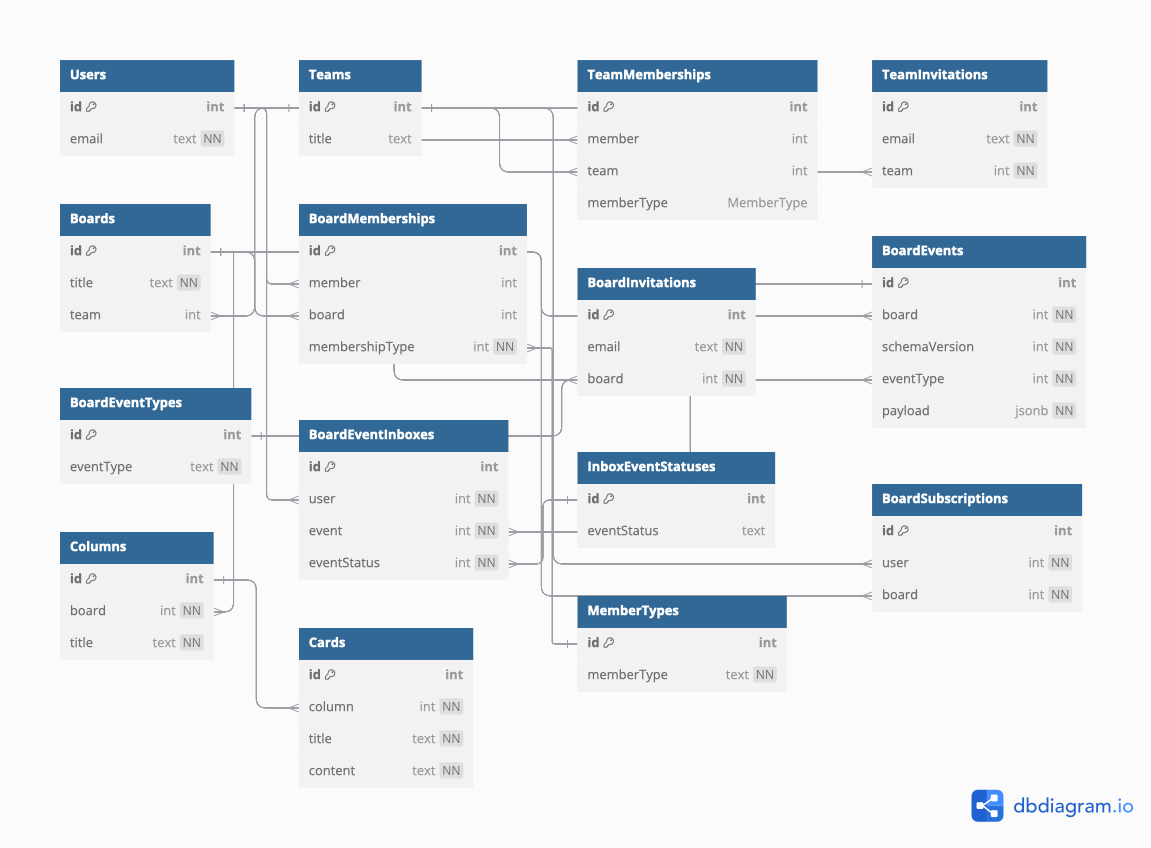

Example: ZenKanban

Continuing the Zenkanban example from the previous post, here is the new model. It’s been updated to support notifications for boards. The schema is growing now in total complexity. However, it is still easy to focus on a particular subsystem such as memberships or notifications without needing to necessarily engage with the system as a whole. That kind of logical distinction is vital for building stable and extendable systems.

table Users {

id int pk

email text [not null, unique, note: "Always lowercase"]

}

table Teams {

id int pk

title text

}

table TeamMemberships {

id int pk

member int [ref:> Users.id]

team int [ref:> Teams.id]

memberType MemberType

Indexes {

(member, team) [unique]

}

}

table TeamInvitations {

id int pk

email text [not null]

team int [ref:>Teams.id, not null]

}

table Boards {

id int pk

title text [not null]

// If there's no team relation, it's a private user board

team int [ref:> Teams.id, null]

}

table BoardMemberships {

id int pk

member int [ref:> Users.id]

board int [ref:> Boards.id]

membershipType int [ref:> MemberTypes.id, not null]

Indexes {

(member, board) [unique]

}

}

table BoardInvitations {

id int pk

email text [not null]

board int [ref:>Boards.id, not null]

}

table BoardEvents {

id int pk

board int [ref:> Boards.id, not null]

schemaVersion int [not null]

eventType int [ref:>BoardEventTypes.id, not null]

payload jsonb [not null]

}

table BoardEventTypes {

id int pk

eventType text [not null]

}

table BoardEventInboxes {

id int pk

user int [ref:>Users.id, not null]

event int [ref:> BoardEvents.id, not null]

eventStatus int [ref:> InboxEventStatuses.id, not null]

Indexes {

(user, event) [unique]

}

}

table InboxEventStatuses {

id int pk

eventStatus text

}

table BoardSubscriptions {

id int pk

user int [ref:>Users.id, not null]

board int [ref:> Boards.id, not null]

Indexes {

(user, board) [unique]

}

}

table Columns {

id int pk

board int [ref:> Boards.id, not null]

title text [not null]

}

table Cards {

id int pk

column int [ref:> Columns.id, not null]

title text [not null]

content text [not null]

}

// Lookup tables

table MemberTypes {

id int pk

memberType text [not null]

}

Recap

The proposed pattern for adding notifications and inbox support is simple. It adds three new tables:

EntityEvents- A NoSQL event log for the entity we’re saving events for. The benefits of storing ajsonpayload for events in a single table outweigh the cons from not modelling each event into a table.EntityEventInboxes- The inboxes track user interaction with the events, and provide a way to calculate which events have not yet been seen by the user.EntitySubscriptions- Tracking subscriptions for an entity like this allows us to support both automatically subscribing a user to an entity they created, and add features such as requesting updates to an entity.

Even if this pattern is stamped out several times into your database - for instance when adding events for both boards, and cards in ZenKanban - it only marginally increases the total complexity of the system.

The actual application layer action handlers for each record need only concern themselves with one or two tables (EntityEvents, and EntityEventInboxes if suppressing an event).

Taken individually like this, the cognitive load remains low. That is what matters when building complex systems. Composition of simple elements such as this pattern allows us to split the whole into loosely connected subsystems that are easy to reason about.